IV fluid policy

Written by:

Dr Jonny Wilkinson– Consultant in ITU and Anaesthesia and NICE IV Fluid Lead

Dr Lisa Yates – Clinical Fellow in ITU

Additions from Dr Ashley Miller (@icmteaching).

Legal pre-amble!

I would like to point out to everyone before we go any further on here, that the IV fluid guideline discussed below has NOT YET BEEN APPROVED BY NORTHAMPTON GENERAL HOSPITAL. I am happy for you all to download a copy to use within your trusts, provided appropriate approval is sought. Also, again, these are not the views of Northampton General Hospital. There we are…..done!

I would like to thank Prof. Manu Malbrain for all of his help in extensively reviewing/contributing to our guidelines. Much of it was published in the text below:

Click below to download a copy:

Background

Summary

This post aims to guide clinicians through the assessment and management of patients requiring IV fluids. It aims to aid in the management of electrolyte replacement and minimise the potential harm to patients from fluid mis-management.

It incorporates much of this publication:

Introduction

Intravenous (IV) fluids are some of the most commonly prescribed day-to-day drugs. They have their indications, benefits, risks, side-effects and complications. Often, the task is delegated to the junior most members of the team. Evidence suggests that such prescriptions are rarely ever done correctly despite the presence of clear guidelines. This is thought to be due to lack of knowledge and experience, which often breeds confusion. Consequently, this puts patients at increased risk of serious harm and may incur unnecessary costs to hospitals.

It is therefore imperative to carefully assess the individual, their requirements and the clinical picture in order to tailor IV fluid plans safely.

Ideally, fluids should be prescribed on the ward-round by the team who knows the patient and their history. Non-parent team prescriptions, particularly out-of-hours, require extra care and in particular should not be done as a duplication of the last prescription in order to save time.

Clearly, there are emergent situations whereby fluids need to be prescribed outside of this policy.

The problem

Previous retrospective reviews of prescriptions within our Trust have identified poor control of the process. There were considerable variations in IV fluid prescriptions; none of which adhered to NICE guidelines. At times, some prescriptions were placing patients at increased risk of associated complications. The knowledge base amongst medical staff regarding IV fluids was extremely variable, sometimes poor.

- Fluid Volumes

- 16% had the correct volumes prescribed for maintenance fluids.

- Electrolytes & Glucose

- Patients received excessive amounts of sodium within their IV fluid prescriptions, yet minimal potassium.

- Only 25% contained the correct amount of glucose.

- Production of a new IV fluid bundle (Click below to download), led to significant improvements in the measured outcomes and balancing measures.

- After the bundle introduction:

- All patients had a documented review of both fluid status and balance

- The incidence of deranged U&E’s decreased from 48% to 35%

- The incidence of AKI decreased 14% to 10%.

- The average number of days between the latest U&E’s and a fluid prescription decreased from 2.2 days to 1.0 day.

Clinical guidelines

Target Group

The guidance was designed to grab the attention of key users in our trust:

- All patients considered for maintenance IV fluids:

- Those with existing or developing deficits that cannot be compensated by oral intake.

- When fluids are lost via drains or stomata, fistulas, fever, open wounds (including evaporation during surgery), polyuria (salt wasting nephropathy or diabetes insipidus).

- With the overall aim – to match the amount of fluid and electrolytes as closely as possible to the fluid that is being or has been lost.

Exclusions

- Patients under the age of 16 – consult your trust’s paediatric team

- Diabetes/DKA – use your trust’s current diabetes guidance or diabetic emergency guidance

- Burns – use your trust’s existing burns calculations

- Obstetrics – discuss with senior obstetric team for more complex patients

- Head injury – avoid fluids containing glucose and liaise with a neurotrauma centre if you are not already one

- Renal/Liver patients – discuss with senior gastro./renal team

- ITU patients – managed by the ITU team

- Elective and emergency theatre cases – managed by the anaesthetist caring for the patient in theatre. Relevance to this policy comes in post-operative ward management.

Background Clinical Physiology

We often give too much IV fluid and in particular, too much non-physiological salt. Once within the body, such non-physiological excesses are very difficult to remove and can result in many adverse situations for our patients.

There are extremes – increased fluid load can cause major electrolyte swings, whereas dehydration, left unchecked, can lead to poor organ perfusion.

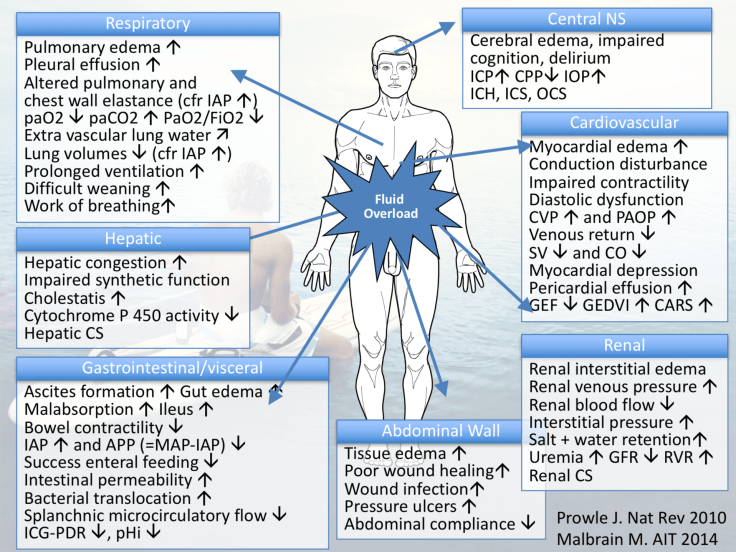

Sick patients (particularly those with systemic inflammatory response syndrome or ‘SIRS’ and those with sepsis), have ‘leaky capillaries. In this situation, even careful IV fluid administration can lead to fluid overload and resultant complications associated with it, (ileus, poor mobility following peripheral oedema, pressure sores, pulmonary oedema, poor wound healing and anastomotic breakdown). This is because the administered fluid escapes from the intravascular compartment (the patient does not ‘hold onto it as expected’), flooding the extracellular compartment where it offers no physiological benefit to the patient.

Organ perfusion (blood flow), is dependent on the pressure gradient from the arterial to the venous side of the organ. Arterial flow is constant over a wide range of blood pressures due to auto-regulation. Therefore organ blood flow is dependent on venous pressures. Hypervolaemia increases venous pressures and reduces organ blood flow, as it increases downstream pressure, effectively clogging up the system! It has been well demonstrated that AKI is often a direct result of fluid overload!

These patients are too often labelled as hypovolaemic, but technically they are not. We have a situation whereby fluid has escaped into another body compartment away from its beneficial site within the circulating volume. What these patients require, after sensible fluid challenges and identification of ‘non-response’, is early consideration of vasopressor therapy (i.e. noradrenaline). This is why in sepsis and states of critical illness, poor IV fluid prescribing practice can ultimately lead to morbidity (See figure 2), and even worse, mortality.

Check out many of Manu Malbrain’s slides on the issues of fluid overload below!

We often look at urine output as a marker of fluid requirement, however patients who are unwell, have suffered trauma, or have undergone surgery often have a reduced urine output due to increased sodium retention (and thus water), by the kidneys. This is a Neanderthal stress response and is geared to holding on to intravascular volume in order to maintain vital organ perfusion during such stress states. Stress induced (‘inappropriate’) anti-diuretic hormone secretion, as well as intrinsic vasopressor hormone secretion, lead to a state of sodium retention and potassium loss in the urine. The patient becomes oedematous, hypokalaemic and hypernatraemic over time, if left unchecked. If normal saline has been given as a resuscitation fluid or maintenance fluid, the potential situation of hyperchloraemic acidosis can ensue, on top of these other electrolyte imbalances.

No patient should suffer the effects of cellular dysfunction and ultimately multi-organ dysfunction, as a result of excessive IV fluid provision. Armed with an understanding of fluid physiology, one can see why oliguria is a poor marker of fluid requirement. Physiological oral fluids should always be first line, unless circumstances absolutely disallow it.

“Then best fluid may be the one that has not been given…(unnecessarily)”

Considerations prior to all IV fluid prescriptions

- Patient’s fluid status(hypo/eu/hypervolaemia) — Assess as you are there!

- Clinical judgement, vital signs and fluid balance including urine output.

- Patient’s weight — Within last 4 days, if none, get a weight!

- Patient’s Urea and Electrolytes — Within last 24 hours. If none, draw blood now!

- Patient’s fluid balance charts (Input and output) — Over the last 24 hours

Prescription safety can be summarised by the ‘4 D’s’ principle (Malbrain L.N.G):

- Drug– which fluid

- Dose– calculate how much to go via a pump

- Duration– duration of the IV fluid therapy

- De-escalation– stop it as soon as possible.

“Give the Right fluid to the Right patient at the Right time”

1. Fluid status

- Basic history and examination of the patient will give pointers as to what their volaemic status is (See Table 1).

- The best fluid to give is physiological fluid i.e. oral fluid. Always consider this first.

- ***Advanced users may utilise non-invasive cardiac output monitoring, or point-of-care ultrasound to extend the assessment of patients. This is without the scope of this guideline and many of these are still under intense debate.

- See our POCUS sections on this site to dig into this a little more.

2. Weight

- It is important to record patient weight at least once per week.

- Weight gain should not be due to excessive IV fluid loading (provided there is no other obvious reason for weight gain).

- Fluid overload

- Dividing the cumulative fluid balance in litres, by the patient’s baseline body weight x 100%, defines the percentage of fluid accumulation.

- Fluid overload is defined by a cut-off value of 10% of fluid accumulation, as this is associated with worse outcomes.

3. U&E levels in the last 24 hours

- Patients who are being considered for IV fluid therapy should have documented U&E results within the last 24 hours. If not, levels should be taken as soon as possible.

- This is to gauge both the effects the exogenous fluid will have over time on the patient’s electrolyte levels and to ensure inappropriate fluid is not administered to them (Potassium containing fluid if hyperkalaemic/sodium containing fluid if hypernatraemic etc).

4. Fluid balance in the last 24 hours

- Fluid balance is key. All patients should have accurate input/output charting. Clearly, it is more difficult to do this precisely in those who are not catheterised.

- Review recent history –

- Losses:

- Fasting, operations, sepsis, excessive sweating in febrile states, diarrhoea and vomiting

- Upper G.I losses in excess i.e. vomiting, tend to lead to states of alkalosis, potential electrolyte disturbance and ‘true’ dehydration.

- Lower G.I losses in excess i.e. diarrhoea, tend to lead to states of acidosis, potential electrolyte disturbance including hypokalaemia and true dehydration.

- Gains:

- Fluid overload states (oedema and excessive positive balance)

- Normal intake

- Is the patient eating and drinking adequately? The best fluid is physiological fluid…i.e. oral intake.

- If patients are not nil by mouth and are not suffering with excessive losses, requests to prescribe IV fluids should be challenged.

- Fluids are drugs and they should be held in equal esteem.

- Recorded losses

- Is the patient is losing, has lost fluid, or isn’t drinking appropriately? Classic examples are recorded excessive stoma output, vomiting, diarrhoea, excessive sweating etc.

- Fasting, operations, sepsis, excessive sweating in febrile states, diarrhoea and vomiting

- Losses:

Consider adding excessive losses to your calculated maintenance fluid. Amount lost in 24 hours divided by 24 to give the amount to add to maintenance per hour.

Fluid prescription – work out what you need!

Which IV fluid?

- Knowledge of IV fluid constituents:

- Be wary of what each bag of fluid contains. Many IV fluids contain a lot of sodium! (See table 5)

- Fluid of choice

- 0.18% saline with 4% dextrose with/without potassium

- At the correct rate, this should give a balanced solution.

- Be mindful of the fact there is no potassium in this solution and it must be added if the patient is hypokalaemic.

- Excessive amounts can cause hyponatraemia/hypokalaemia.

- Hartmann’s solution/Ringer’s lactate/Compound sodium lactate

- Again, a balanced safe solution.

- If the patient already has a sodium of less than 132 mmol/l, the use of Hartmann’s for maintenance may be the preferred option.

- Contains potassium.

- Do not use this if the patient has hyperkalaemia

- **Potassium supplementation**

- Can be added to 0.18% saline with 4% dextrose and normal saline

- Can be added to 5% dextrose (though we strongly discourage this fluid’s usage in maintenance/resuscitation).

- Do not add to Hartmann’s!

- If the serum potassium is already greater than 5mmol/l, do not add in extra potassium to any IV fluid

- All potassium containing fluids should be administered via an appropriate volumetric pump.

- Re-feeding syndrome

- Consider Pabrinex if the patient is at risk of refeeding syndrome, (take this volume into account when calculating their maintenance)

- 0.18% saline with 4% dextrose with/without potassium

DO NOT USE 5% DEXTROSE AS A MAINTENANCE FLUID!

DO NOT USE COLLOIDS AS A MAINTENANCE FLUID!

DO NOT USE 0.9% (Ab)NORMAL SALINE FOR ANY PROLONGED PERIOD.

1. Maintenance fluid

Important points

- Enteral and parenteral feed

- The patient may not the entire calculated maintenance dose per hour if receiving enteral feed and in particular, TPN.

- Time fasting or NBM

- Consideration should be given to maintenance fluid in any patient fasted for over 8 hours.

- Drugs add in fluid!

- Many IV drugs are administered with large amounts of fluid. These can add large amounts to a calculated maintenance rates if forgotten about.

- If patients are hypervolaemic

- They may require fluid restriction or diuresis.

- Other excessive losses

- Some may be more occult, like febrile states leading to excessive evaporative losses in sweat. Consideradding these to your hourly maintenance rate.

- Replacing urinary losses

- Urine does not need to be replaced unless excessive in volume (i.e. in the with diabetes insipidus or the diuretic phase of resolving renal failure).

- Surgical stress response

- In a post op patient, polyuria may be multi-factorial. It may be due to excessive intra-operative fluid provision, or secondary to the surgical stress response itself. Here, increased anti-diuretic hormone release from leads to retention of sodium and water but diuresis of potassium containing urine.

- Prescription inaccuracy

- Try and avoid prescribing fluid bags over x number of hours; instead prescribe in ml/hr. All patients receiving IV fluids for over 6 hours, or those receiving potassium replacement, should all have fluid delivered via a volumetric pump.

- Do not crank up maintenance fluid rates!

- Maintenance fluid should not be given at a rate greater than 100ml/hr. Try to avoid ‘speeding up’ infusions if patients are deemed to be ‘non-responders’. This is where IV fluid challenges come in.

NEVER ADJUST IV MAINTENANCE RATES IN ORDER TO PROVIDE A FLUID CHALLENGE!

These are often left running at the challenge rate, resulting in severe fluid overload. Use a prescribed fluid challenge separately.

2. Resuscitation Fluid

- For urgent resuscitation

- We recommend the use of crystalloid.

- Hartmann’s solution (Compound Sodium Lactate/Ringer’s lactate) is a good choice as it is well balanced.

- 18% NaCl/4% glucose is a good alternative; however, care is needed as this does not contain potassium. This may need to be added if the U&E profile suggests it.

- We do not recommend

- The use of 0.9% sodium chloride. This is a poor choice of IV fluid in shock states with acidosis, as it will potentially worsen the situation (causes hyperchloraemic acidosis). It has a supra-physiological sodium content and is NOT ISOTONIC.

DO NOT USE 5% DEXTROSE AS A RESUSCITATION FLUID!

- Colloids

- Colloids can be dangerous! (High sodium load, incidence of allergic reactions etc).

- Crystalloids are fine to use.

DO NOT USE COLLOIDS FOR RESUSCITATION

- Bleeding

- The priority is to locate and stop the bleeding.

- The best replacement for this is blood and any accompanying blood products.

- Consider initiating the massive haemorrhage protocol through your switchboard.

- Sepsis and septic shock

- Evidence is mounting against excessive fluid resuscitation in this group.

- What many of these patients require is earlier vasopressor support in a critical care environment, or certainly early advice from a senior member of the team/critical care failing this.

- If in excess of 2000ml IV fluid challenge has been provided, escalate to more senior medical personnel, rather than continuing to pour in fluid. The more fluid a septic patient receives, the higher the morbidity and mortality is likely. It may be prudent to liaise with critical care if the situation is deemed complex.

!!!Surviving Sepsis Campaign…drowning the masses??!

- We recommend caution over the usage of 30ml/kg resuscitation fluid dosage (as recommended by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign), for ALL patients.

- This has been debated worldwide now, and the predominant expert opinion is that this may be excessive.

- It may be applicable to those who are profoundly shocked with sepsis/SIRS, but should always be paralleled with appropriate escalation and advice from more senior clinicians.

We recommend starting with 4ml/kg over 5 minutes and assess the response.

-

Facts:

- Less than 50% of haemodynamically unstable patients are ‘fluid responders’

- It is unproven in humans that fluid boluses in septic shock improves cardiac output or organ perfusion.

- 85% of an infused bolus of crystalloid goes to interstitial space after 4 hrs in health.

- This increases to 95% in sepsis and in under 90 minutes!

Difficult situations and tips

- Use a natural fluid bolus to assess volume tolerance

- Consider response to 45˚ passive leg raise (See Figure 3)

- This is a very simple way of creating an auto-transfusion to your patient.

- The legs contain a venous reserve of around 5-600ml.

- After the manoeuvre (wait 30-50 seconds), did the patients BP rise and pulse rate drop? When reverted back to seated, does the BP and pulse rate revert to pre-manoeuvre state.

- If ‘yes’ – volume tolerant

- If ‘no’ – look for other reasons for the observations, they are not hypovolaemic!

- Consider a urinary catheter in all sick patients.

- Signs of hypovolaemia may be unreliable in:

- Elderly patients

- Often on concomitant drugs slowing heart rate e.g. Beta blockers. This may attenuate any pulse rate responses.

- Normal blood pressures in the elderly may be low for them if they are normally hypertensive.

- Cardiac pathologies and dysautonomic states can cloud responses to fluid challenges and hypovolaemic states.

- Young fit patients

- Have a high physiological reserve capacity.

- They have a rapid adrenergic compensatory pressure response to intravascular volume loss. Therefore, much delayed vital sign deterioration.

- This is also why looking at CVP one-off values is useless most of the time.

- The initial response to a volume loss in prior fit individuals is secretion of endogenous catecholamines. This causes a PRESSURE increase in the vascular beds. Thus CVP will go up initially.

- Excessive losses

- Calculate the losses over the previous 24 hours.

- Consider replacement using an appropriate crystalloid.

- If upper GI loss, use 0.9% NaCl +/- KCl, or 0.18% saline with 4% dextrose +/- KCL.

- See table 6 for electrolyte emergencies

- Hyponatraemia: The causes of this are varied and complex. A sodium less than 125mmol/l can be dangerous and senior input should be sought.

- Potassium: Just because the potassium level is normal, does not necessarily mean that there isn’t a deficit, therefore consider adding it to replacement fluid.

- Elderly patients

Escalation of the non-responder and Critical Care

Consider discussion with critical care if:

- GCS </=8 or falling from a higher level

- Suggestive either of severe shock or another cause for decreased conscious level.

- O2sats lower than 90% on 60% oxygen or higher

- Suggestive of either cardiorespiratory pathology or fluid overload state!

- PaCO2>7kPa unresponsive to NIV/CPAP

- As above

- Persistent hypotension and/or oliguria unresponsive to 2l fluid and/or concern of cardiac function.

- May be prudent to consider offloading excess fluid with more advanced monitoring / equipment and experienced personnel available.

- Metabolic acidosis: base deficit -8 or worse, bicarbonate <18mmol/l, lactate >3mmol/l and not improving in 2 hours with treatment.

- Suggestive of severe shock state

- Complex pathologies/disease states requiring closer monitoring than a ward-based level 0 setting can offer.

Click the graphic for a copy!

Roles and responsibilities

Closing comments:

Please use all of these resources to help you out. They are all here in order to aid in the prevention of any adversity for patients receiving IV fluids. Comments on any of this; please let us know. wilkinsonjonny@me.com

Happy Safe Prescribing!!

To come:

- IV fluid algorithm infographic

- More infographics relating to fluid overload states

- Updates on the IV fluid guidelines

More resources:

1. A great discussion of like minded clinicians on the subject!

2. Another I triggered with the thinking cap on!

3. Previous post on audit and investigation into IV fluid misuse situations!

4. Case based discussion on advanced techniques to assess your patients!

5. Fluid types, deresuscitation and more

If you click on the ‘Fluid’ tab within the tag cloud below, you can dig about into other posts from us on trials, cases and more on IV fluids.

Jonny this is great stuff! Can we podcast this???